Sagami, Japan’s leading condom company, conducted a survey on sex in Japan in 2013. Their results are highly interesting, and I always refer to them. However, there doesn’t seem to be enough information in English, so I decided to write about it.

The survey was conducted in January 2013 with 14,100 respondents with an equal distribution of age (20s through to 60s), sex, and location (prefecture). The respondents completed the survey online.

By the way, Sagami makes fantastic condoms. Even though I tend to go for Okamoto, another top-notch condom company in Japan, both companies are great. I’ve never come across condoms as good as theirs. If you know any better ones, please let me know!

Marriage and Relationships: Japanese people don’t date much but they get married nonetheless

Question: Are you married? If you are not, are you in a relationship?

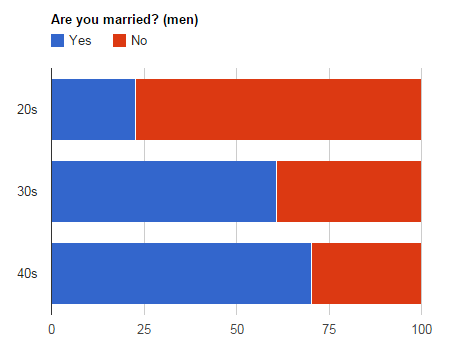

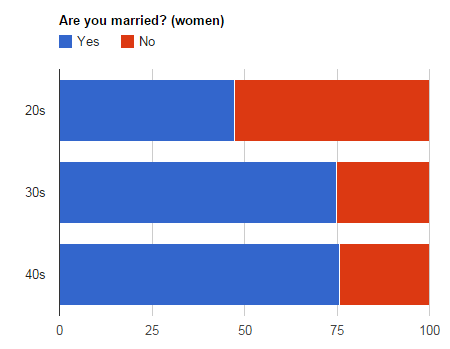

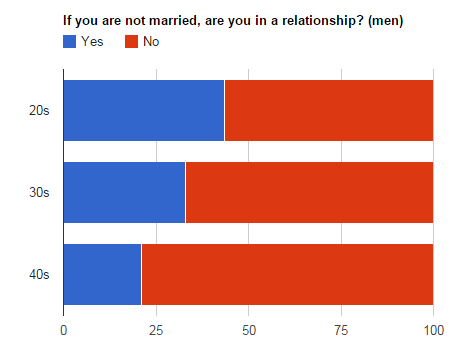

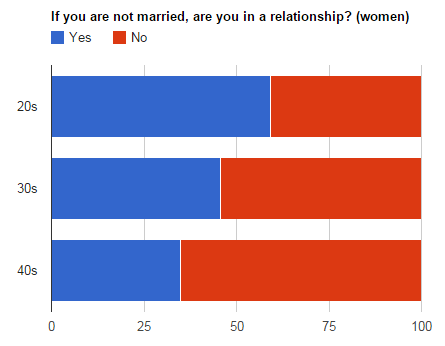

Results: 22.6% of the twenty-something men are married as opposed to 60.7% of the thirty-something men. As for women, the percentages are 47.2% for twenty-something and 74.8% for thirty-something.

56.4% of Japanese unmarried men in their 20s are single, while 67% of Japanese men in their 30s are single. As for women, the numbers are 40.9% (20s) and 54.4% (30s).

Now, consider this: while 43% of the men in their 20s are single, the number of singles goes down to 26.3% of the men in their 30s. I think this is partly because marriage is generally more important than dating in Japan.

‘Dating’ is a fairly new concept in Japan. For example, we don’t have a proper Japanese word for ‘to date’. (We just use deto, which is just the Japanese pronunciation of ‘date’.)

I remember that in my Japanese high school, not many people were dating. Even if they were, they didn’t talk about it a lot, and couples were not visible in school. I never felt any pressure that I had to date somebody. I did date somebody, but I hardly ever discussed it with my classmates.

But, when it comes to marriage, it’s a different question. When you are in your late 20s or in your 30s, people start asking you questions: When are you going to get married? Why aren’t you married? People start introducing you to your future husband or wife. My boss did that

to me once.

The Japanese tend to have very different attitudes towards dating and marriage.

Sex Frequency: Yes, Japanese people have sex infrequently

Question: If you have a sexual partner, how many times do you have sex per month?

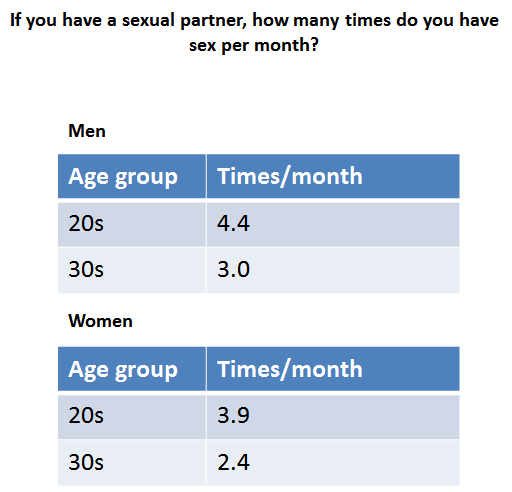

Results: On average, when they are married or in a relationship, men in their 20s have sex 4.4 times, in their 30s, 3 times, and in their 40s, 1.9 times a month. Women in their 20s have sex 3.9 times, in their 30s, 2.4 times, and in their 40s, 1.6 times a month.

As for the differences between relationship statuses, married people have sex 1.7 times a month on average, unmarried couples 4.1 times, and sex friends 2.9 times. The overall average is 2.8 times a month.

Do you remember the Durex sex survey in 2005? According to their survey, Japanese people have sex 45 times a year on average, which translates to 3.75 times a month. But Durex didn’t seem to limit the respondents to the ones who had sexual partners, while Sagami did. So if Sagami did the survey with the same conditions as Durex, the average sex frequency would be much lower than 2.8 times.

Japan’s number, 45, is 28 points less than the second least sexually active nation, Singapore, and 93 points less than the most active nation, Greece. Japan is a complete outlier.

These are self-reported surveys online, so we don’t know how accurate the results are. But considering the information we have so far, the most logical conclusion is that Japanese people have significantly less sex than people in most developed countries.

Sexless: 55.2% of the married couples are sexless

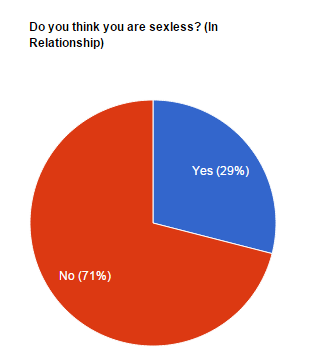

Question: Do you think you are sexless?

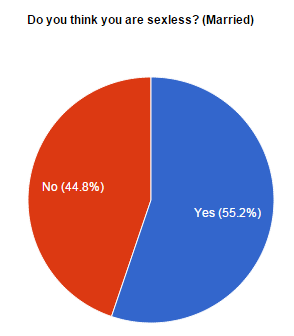

Results: 55.2% of the married couples and 29% of the unmarried couples think they are sexless.

In my opinion, being sexless is a problem only when you are not happy with it, so let’s look at the next statistic.

Sexless: 69.7% of the people in a sexless marriage or relationship want to have sex

Question: If you are sexless, do you want to have sex?

Results: 75.2% of the sexless men and 64.2% of the women still want sex.

In other words, 30.35% of the sexless people don’t really want to have sex. Nonetheless, more than two-thirds of the people are in an unhappy sexless marriage or relationship. This is quite unfortunate.

Sexless: The biggest reason that they are sexless is that their partners don’t want to have sex

Question: If you are sexless but want to have sex, why don’t you have sex?

Results: About 40% of the sexless people say their partners don’t want to have sex. About 30% of them say they are too busy or tired. About 23% say having children or family members in their house makes it difficult. (Japanese apartments and houses tend to be small.) About 18% of them say they don’t desire their partner anymore.

Sexless: Many people who don’t want to have sex think sex is too troublesome

Question: If you don’t want to have sex, what is the reason?

Results: About 40% of men and 50% of women say having sex is too much trouble. About 25% of men and 40% of women say they have very low libido. About 30%

of men and women say they are too tired to have sex.

‘Too troublesome’ or mendoukusai is a very Japanese expression; they don’t necessarily dislike sex, but they think it’s probably not worth it considering the effort they need to make.

Sexual Desire: More than 80% of the single men want to have sex

Question: If you are single, do you want to have sex?

Results: About 83% of the single men and 58% of the single women in their 20s and 30s want to have sex.

In recent years, Japanese men seem to be gaining a reputation of having a low sex drive. However, the survey shows that more than 80% of single men want to have sex. Of course, you can say 80% is not a lot, but to me, it doesn’t seem too weird that 10 to 20% of them have a low sex drive.

Also, the survey says that 36.9% of the people with a low sex drive still want to be in a relationship even though they don’t really want to have sex.

Sexual Partners: Japanese men have 10+ and women have 5+ sexual partners

Question: How many sexual partners have you ever had?

Results: On Average, Japanese men in their 20s had 7.4 sexual partners, and the men in their 30s had 11 partners. The averages for the women were 5.5 (20s) and 6.8 (30s).

These numbers don’t seem particularly small to me.

We have seen various stats so far, but the only area where Japan is clearly an outlier is the frequency of sex. But otherwise, Japanese people want to have sex and sleep around like everyone else.

Infidelity: About 20% of the people cheat

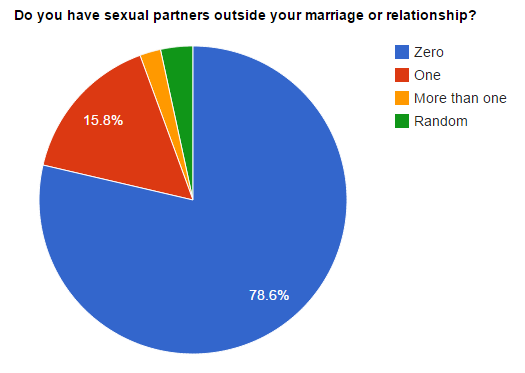

Question: Do you have sexual partners outside your marriage or relationships?

Results: 78.8% of the respondents say they don’t have any extra-marital or extra-relational partner. 15.8% say their have one partner, and 2.2% say they have more than one partner. Also, 3.4% say they don’t have fixed partners.

The question didn’t ask if their main partners know about their extra-marital or extra-relational affairs. But, assuming that most cases are not consensual, we can say that about 20% of the people are cheating.

Infidelity: Japanese people have fun with co-workers

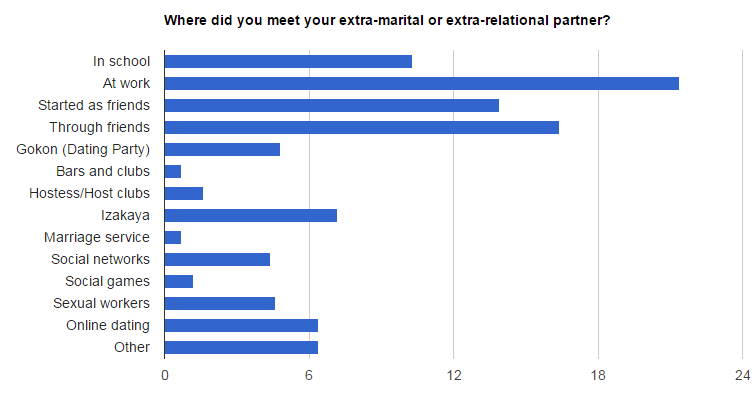

Question: Where did you meet your extra-marital or extra-relational partner?

Results: 21.4% of the respondents met their sexual partner at work, 16.4% of them met through common friends, and 10.3% met in school. Relatively few people were total strangers and only 0.7% of them met in bars and clubs.

If you are a western person and hang out in bars and clubs in Tokyo, you might meet potential sexual partners there. But be aware that the Japanese people who frequent those places are in the minority.

There is another survey that asked where Japanese people meet their spouses. The results are quite similar: at work, in school, and through friends.

Virginity: Less than 10% of the thirty-something people are virgins

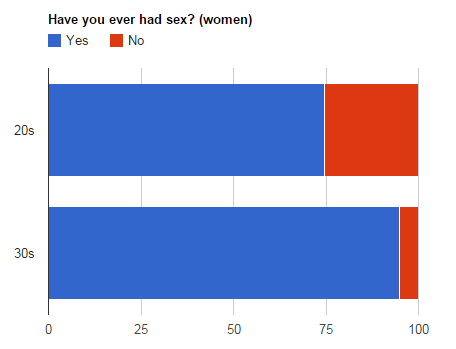

Question: Have you ever had sex?

Results: 40.6% of men in their 20s are virgins, but the number goes down to 9.5% for thirty-something men. 25.5% of the women in their 20s and 5.1% of the thirty- something women are virgins.

These numbers seem to be in line with the relationship/marriage results: Japanese people don’t date a lot when they are in their 20s, and many of them get married when they reach 30.

Also, Japanese kids don’t have much privacy. Japanese houses and flats tend to be small, and even if they have their own rooms, they often don’t have locks, and walls are very thin. So when they live with their parents, having sex is difficult. Of course, you can always go to love hotels and rent a room by the hour. But love hotels are quite expensive for high school students.

Virginity: Japanese people lose their virginity in their late teens

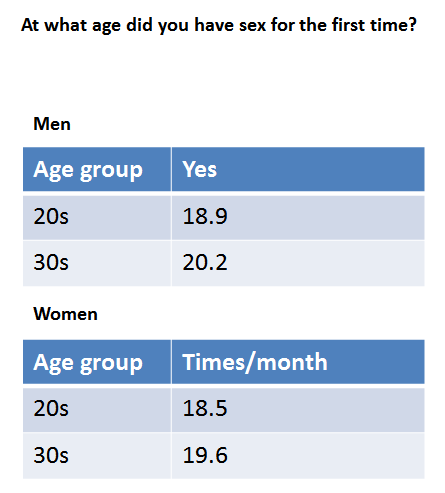

Question: At what age did you have sex for the first time?

Results: On average, the men in their 20s lost their virginity at 18.9, and the men in their 30s lost it at 20.2. As for women, the average ages are 18.5 (20s) and 19.6 (30s).

I think these numbers mean that Japanese people tend to lose virginity when they start going to university when they are 18 or 19.

Masturbation: Japanese men in their 20s masturbate 11.1 times a month

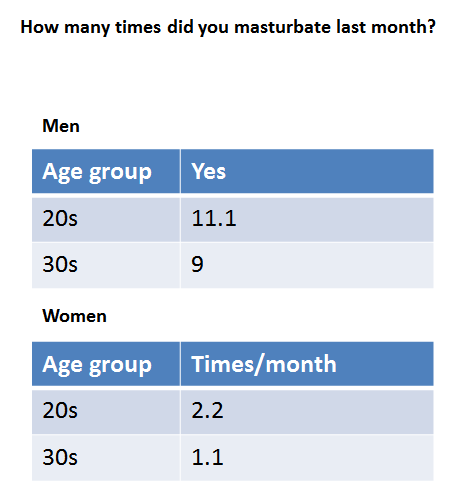

Question: How many times did you masturbate last month?

Results: On average, the men in their 20s masturbate 11.1 times a month, and the men in their 30s masturbate 9 times a month. The averages for women are 2.2 times (20s) and 1.1 times (30s).

I don’t really know what to make of these numbers, but, nonetheless, I find them interesting. One thing that is sure is that Japanese men will never run out of porn to watch, given the huge quantity available…

If you are interested in sex in Japan, I would recommend my new book There’s Something I Want to Tell You: True Stories of Mixed Dating in Japan.